Sneakers and basketball have always been synonymous. No matter the brand, each one has had its moment on the hardwood and beyond. From championship headlines to pop culture moments, the symbiotic relationship between sneakers and basketball is instrumental in understanding and appreciating the value they bring.

Alex Wong, a respected writer with bylines ranging from SLAM to GQ, has gone back in time with his new book that dives into the stories behind our favorite cover stories. Cover Story The NBA and Modern Basketball as Told Through Its Most Iconic Magazine Covers is a trip down memory lane that not only covers the game we all love but taps into the culture fueled by sneakers.

We had a chance to chop it up with Wong and discuss his ascension into sports writing, the inspiration behind the book, and giving a glimpse behind some of the chapters.

Read what Wong had to say in our exclusive one-on-one interview below. Be sure to get a copy of Cover Story, available here and at select bookstores.

SoleSavy: How did you start writing about basketball?Â

Alex Wong: I went to school for business. In my 20s, I was a chartered accountant. 9-5 job. I always loved basketball, and I always loved writing. Towards my late 20s, I quit my career to pursue freelance writing. I grew up in Toronto and moved to new york for a period of time to see if I could pursue this career. I got some good breaks and had people set me up with some opportunities. I started writing for Complex, Dime Magazine and became a recurring contributor for SLAM magazine.

Eventually, I moved back to Toronto and have been covering the Raptors. It’s been a lot of hard work and making connections in finding my niche in this basketball space.Â

I’ve always prided myself as a writer who finds unique, different, off-beat ideas that are not focused on the Xs and Os of the game. There’s a lot of great people who do that work, but it’s never something I’ve been interested in as a writer. I’ve been more about telling other peoples’ stories and the culture surrounding the game of basketball.

Working on this book was right in that sweet spot of something that I could get excited about. I grew up with these magazines; I grew up with these players. Now, I want to tell the story of how these covers came together while giving people the historical context from interviews on why these magazines and their covers are important and matter.Â

SS: What inspired you to write Cover Story?

AW: The origin story of this book started a few years ago. I did an article for ESPN’s The Undefeated; they had a section called cover stories. Writers would pitch ideas telling the behind-the-scenes stories of famous magazine covers. The cover that I pitched and ended up writing was about when Jeremy Lin got back-to-back Sports Illustrated covers. That was such a personal moment for me, being an Asian-Canadian. I always tell people that Linsanity was the Asian Superbowl. Those two weeks were amazing.Â

I had the chance to talk to Pablo Torre, who was at SI at the time and did the feature story. Â I talked to a lot of people within the Asian-American community about representation and what it meant to see someone like Jeremy Lin on the cover of one of the most prestigious and historic sports magazines of all time.Â

After I did that story, it was always kind of in the back of my head that there were so many other magazines covers with behind-the-scenes stories that needed to be told.

When the pandemic hit, I was talking to Cover Story publisher Triumph Books. We had worked on a commemorative 2019 Raptors championship book that was on a smaller scale. More of a coffee table book with some writing and a lot of cool photos. We had conversations about working on other projects. When the pandemic happened, I wanted to revisit and see if there was enough material to do an entire story about magazine covers on basketball.

SS: Were there any challenges when writing this book in the middle of a pandemic?Â

AW: From a technical standpoint, I did over 100 interviews for this book. One of the things I prefer to do when interviewing as a reporter/journalist is face-to-face. Not being able to do that wasn’t necessarily a deterrent. Still, it was a challenge when you’re generally able to be in an environment with that person where the conversations and interactions are always better. Thankfully, once I got acclimated that we were going to be using zoom, it wasn’t as bad as I thought it was going to be.

When I look back on the process of putting this book together for the last year and a half, two years, and most of that in a pandemic, this was a great distraction. As someone who lives a freelance life, I’m used to working from home and all of that, which was a huge adjustment for other people. It was difficult not being able to go to the arena, see my family and friends with regularity. Being able to wake up every day and have this as my big project to work on and segment my day with interviews in the morning, doing errands in the afternoon, write in the evenings: gave me a lot of structure.

Every day I woke up with something on the to-do list for this book. I don’t know if I would’ve hit the deadline or finished the bok in time if it wasn’t for the pandemic because I didn’t realize how much bigger of an undertaking it was in comparison to just planning.

In a strange way, it was kind of a positive.Â

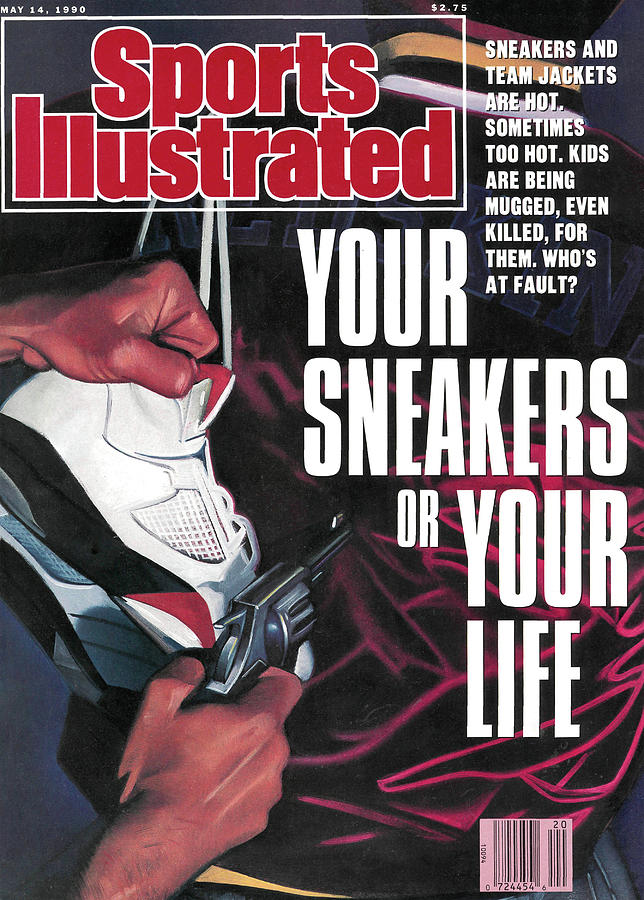

SS: The chapter “Your Sneakers or Your Life” revisits the Sports Illustrated cover from 1990. We see it referenced time after time. But it isn’t an isolated incident in sneakers as violence continues to occur. What was it like to go back in time to see that cover and where the sneaker landscape is today?

(Image via Sports Illustrated)

AW: Going back and reading that cover story and talking to the people involved, and reading some of the newspaper headlines at the time, it feels like nothing has changed. It feels like things are more amplified in a way.

I don’t think it’s fair to say that we should count violent incidents to compare the eras. I believe the more fair comparison is how sneakers are being viewed by the youth today vs. 1990. It’s the exact same. The conversations back then were about how sneakers were being marketed as an unattainable, luxury item. Sneakers are still being marketed as a luxury shoe that’s unattainable, especially when you look at the influencer marketing that’s going on now that was nonexistent a year ago. People still view getting a pair of the most expensive, exclusive sneakers as a status symbol. Some still value the shoe because of a passion for wearing or collecting, but the luxury aspect has gotten completely out of hand.Â

When you look at some of these collabs like the Dior x Air Jordan 1, and you look at the retail prices and then at the aftermarket prices, that’s exactly what was talked about in the SI cover story. These brands continue to position their product as something like a luxury good. I understand the sneaker industry is booming, and it’s working for the companies. Still, at some point, there needs to be an answer to how much responsibility should these sneaker companies have when these tragedies happen? It’s a clear issue of supply and demand. When the demand outweighs the supply, you’re going to see incidents like these happen.Â

I got into sneakers because I watched Michael Jordan on the court. I grew up in the late-80s/early-90s. I saw the sneakers in the dunk contest and during his championships and thought, “these are so cool.”

The Air Jordan 12 “Flu Game” was my favorite because I watched that game. You attach all of these moments to the sneakers. Objectively, if you show me a picture of the “Flu Game” 12s without the context, I’d probably call that an ugly sneaker. But because he did what he did in that game, I don’t care what the shoe looks like because it’s so iconic.

Now, you have the Travis and Virgils and other designers. I don’t hear a lot of people say they got into sneakers because they watched a player. While you look at someone like Kyrie or Giannis, I’m sure they’re penetrating markets since their signature Nike shoes are affordable. But we’ve lost that now. I’m not sure if it’s because of how things are marketed now or if it’s because the Nike basketball line isn’t as strong, but there’s probably not a lot of people out there who will say, “I want those LeBron sneakers because he did this in this Finals game.” This isn’t taking anything away from LeBron. But this is how sneakers are today. I can’t think of a LeBron sneaker that I would tie to a specific moment in his career like I would with Jordan.Â

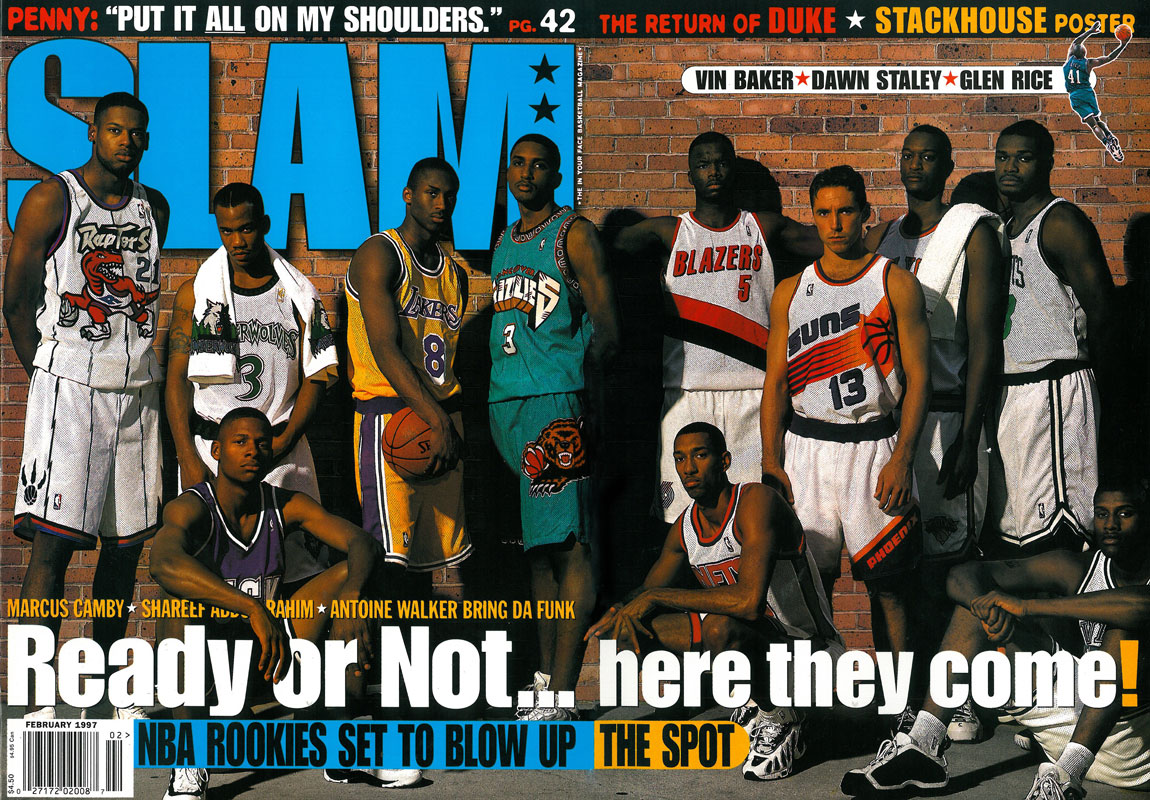

SS: In one of the other chapters, you talk about SLAM magazine — the Mecca, North Star of the intersection of sneakers, pop culture, and sports. What was it like talking to the SLAM greats and digging into their early beginnings?Â

(Image via SLAM Magazine)

AW: I grew up reading SLAM magazine. It was one of those things that you don’t realize until after how influential it was.

Russ (Bengston) goes into detail about how he built the Kicks section up and how he had this interest in sneakers. This was a gateway for them in terms of picking up these cultural interests with basketball. This is how they built the connections with players. That was the fascinating thing. The players, for the longest time, were just depicted in a particular way.

In another chapter, I talk about Allen Iverson and the “Soul on Ice” cover and how the mainstream media had portrayed him differently at the time. For SLAM to make those connections with those players, they’ve been able to forge relationships through sneakers, the music they listen to. You’d never have a Sports Illustrated writer go into the locker room and kick it with the guys like that. But when you have a Russ Bengston walk in with a pair of Nikes that are probably samples the players don’t even have, that’s the best ice breaker; it builds respect. This led to them getting more connections with the sneaker brands.

All of this stuff seems second nature with influencers and sneaker writers and press trips, but it was a groundbreaking thing at the time. The fact that there was a basketball magazine that spoke hip-hop language who covered sneakers, no one was doing that at the time. The SLAM guys claim they were the trendsetters and paved the way for this second wave of sneaker sites and even the makings of a SoleSavy. I’d agree with them. So much of the knowledge about basketball and sneakers came through those SLAM pages.Â

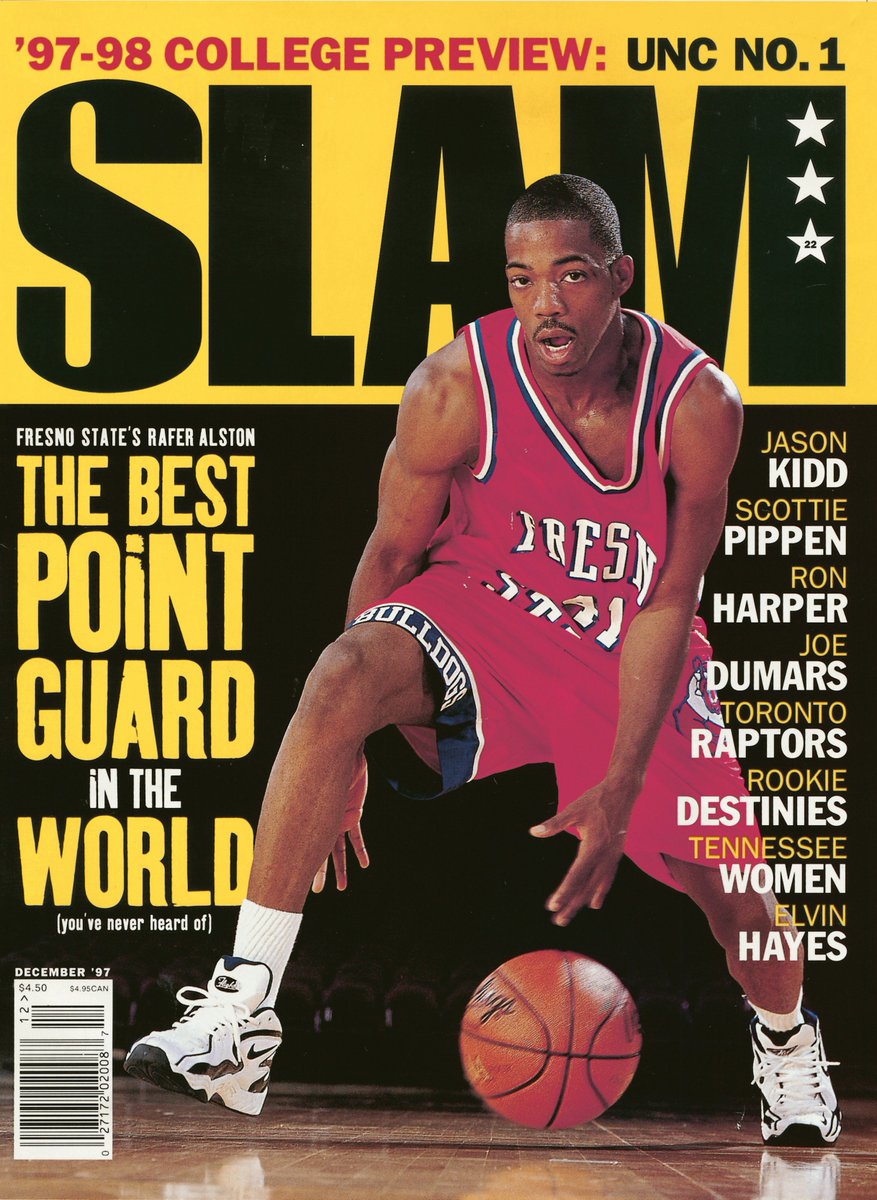

SS: While on the topic of SLAM, another cover, “The Best Point Guard in the World (You’ve Never Heard Of),” goes into the world of streetball and the one and only Skip 2 My Lou. What was it like comping the interviews and digging through the Rucker archives for this part of the book?Â

(Image via SLAM Magazine)

AW:Â I loved tapping into the streetball culture. Being able to talk to DJ Set Free, who was responsible for putting together the first AND1 Mixtape, it was fun to take that trip back. Even though streetball had this mainstream moment with Skip 2 My Lou and AND1, it still came and went in a way. It didn’t have the lasting power that I expected. That’s one of the things that when I think about slam magazine, sure, I think of the ’96 cover and the Iverson cover, but the Rafer Alston cover is one that I remember very specifically getting in the mail as a kid.

You consider yourself a basketball expert. I watched a lot of basketball and read a lot about basketball. But when I saw this kid on the cover, I had no idea who he was. The fact that they (SLAM) had the guts to call him the best point guard in the world was such a visceral thing. It showed the attitude that SLAM had. They were not afraid to be wrong. Sometimes they didn’t care if they were wrong. They knew that he wasn’t the best in the world. They knew as a New York magazine that Skip 2 My Lou was killing the Rucker, and streetball is at the heart of New York. It was fun. It was one of those chapters that, throughout the rest of the book, I made a conscious effort to throw in a little basketball history as well.

It’s important to have an understanding of the context. Streetball did not start with Rafer and did not end with him. To trace that back to the history of the Rucker and give a shoutout to AND1 was huge. The brand shouldn’t be forgotten because the kids often look at it now and either laugh or shrug at it. Vince Carter in the Tai Chi’s was such a sentinel moment. AND1 had such an impact with its mixtape tour. It was important to note that because SLAM often gets associated with hip-hop and sneakers, but they also played a role in introducing a young audience to the streetball scene. Before the internet and YouTube, it was word of mouth. It was cool to be able to tap into that scene.

There’s this beauty about telling people that they had to be there. These guys were superheroes.Â

SS:Â What’s been the most rewarding part of Cover Story?

AW:Â Having the honor to tell their stories.

Anytime you put together a feature, it’s the writer’s responsibility to tell other peoples’ stories responsibly. The thing I get the most satisfaction from putting this book together is having the opportunity to properly tell the story of a Sports Illustrated, SLAM magazine. There’s stuff that even covers The Source and their sports magazine, Sports Source. It’s gratifying for me to get all of these people in to trust me to tell me their stories about what the magazines meant to them.Â

Whether a huge basketball fan or a huge magazine fan, I hope there’s something in the book for you. This wasn’t just about taking a bunch of random magazine cover stories, but I wanted to weave a whole story on how basketball as a cultural thing changed from the 80s to the 90s to the 2000s.

It was just the satisfaction of being trusted to tell other peoples’ stories.Â

A big thank you and congratulations to Alex Wong for his book. Cover Story The NBA and Modern Basketball as Told Through Its Most Iconic Magazine Covers is available here and at select book stores.Â